October 19, 2021

1958-2021

PLEASE SUPPORT THE DR. JACOB HODGSON MENTORSHIP FUND

To honour the memory of Dr. Jacob Hodgson, UBC Zoology is raising funds to create the Dr. Jacob Hodgson Mentorship Fund with the goal to reach $50,000.00, and endow it in perpetuity. This proceeds of this fund will support an Annual Mentoring Award in memory of Jacob, who was a long time Zoology Research Associate and colleague who many of us worked with. This award has been created to honour his outstanding contributions to mentoring. Jacob was a mentor to so many members of the department but his legacy and impact will be remembered for his mentoring of graduate and undergraduate students. The Zoology mentoring award will reflect this legacy and the ongoing contributions to mentoring that so many of our department carry out. Final decisions on the award process will be made in consultation with the department.

To support the Dr. Jacob Hodgson Mentorship Fund, please click on this link https://give.ubc.ca/jacob-hodgson or contact Sarah Doran-Coelho, Associate Director, Development & Alumni Engagement at sarah.dorancoelho@ubc.ca or 604-827-3536 to make your donation.

———

Obituary:

Born in Accra, Ghana on July 18, 1958, Jacob passed away peacefully on Thursday September 16, 2021 in Vancouver, BC, Canada at the age of 63. He would be sadly missed by his siblings- Abraham Isaac, Priscilla and Angelina, brother-in-law Erasmus, sister-in-law Vivian, uncle, aunties, cousins, nephews, nieces, school mates, and friends in Ghana, Gambia, UK, USA, and Vancouver.

Jacob spent most of his working life (over 20 years) at the Zoology Department, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada as a successful Research Associate. Before moving to Canada, Jacob did a postdoctoral study at the Faculty of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, State University of New York, Stony Brook, USA. He obtained his PhD at the National Institute for Medical Research, Mill Hill, London, UK and his first degree at KNUST, Kumasi, Ghana.

His research interests were in biochemistry, tropical diseases, virology, and epigenetics. His research findings were published in high impact peer reviewed international journals like Cell and Nature.

————

Remembrances from Friends and Colleagues:

Jacob joined my lab as a research associate in 1992 and worked with me until I closed my lab in 2015. He was born and raised in Ghana, did his bachelor’s degree there, and then obtained his PhD in the National Institute for Medical Research in Mill Hill U.K. Jacob completed a post-doctoral fellowship at the State University of New York Stony Brook.

My first contact with Jacob was when he phoned me out of the blue to ask if he could do a post-doctoral fellowship in my lab. I was impressed by how much he knew about my research area, and my research, and asked him why he wanted to come to my lab, rather than the labs of one of the two field leaders, and he replied that he had phoned everyone in the field and that they told him that I was the right kind of guy to work with. Jacob placed people first in his life, and this worked out well for me, as well as him. l remember picking him up at the airport and being impressed by how little luggage he had. Jacob was going to stay with me while he found a place to stay, but he insisted that we go by the lab and cold room so he could see them before we went to my house.

It was apparent from the beginning that Jacob was a scholar. The range of his reading and knowledge was enormous in science and generally. He was detail-oriented, meticulous, rigorous, and cautious about interpreting results. As a consequence, Jacob’s papers were data-rich, and widely respected, but not frequent. His two most important papers in my lab were Hodgson, Argiropoulous and Brock, Molecular and Cellular Biology (2001); and Li, T, Hodgson et al. Epigenetics and Chromatin (2017).

Jacob will be mostly remembered for his wisdom, outgoing personality, infectious laugh, and his curiosity about people and their science. It seemed that Jacob knew everyone, and everyone knew Jacob. When my lab was in the Biosciences building, people would ask me if Jacob worked with me. However, by the time we moved to the Life Sciences building in 2005, the question became “Do you work with Jacob?”

Jacob never married, so most of his social engagement was with the scientists in Zoology and in the Life Sciences Institute. Jacob was the lab Dad, and was the mentor, confidant, advisor, and consoler for my students and technicians. People loved to talk to Jacob, and Jacob loved to talk to them. I thought of him as the village elder that everyone loved, trusted, and consulted.

Jacob kept in touch with his sister Priscilla in Canada, his brother Abraham in the US, and his sister Angelina and other members of his family in Ghana and around the world.

Outside the lab, Jacob had an abiding interest in things Japanese. He obtained a black belt in karate before he came to Vancouver, and after he came to Vancouver took up the Japanese sword form iaido, and played the shakuhachi (an end-blown flute made from bamboo).

Jacob was a devout man in a profane world, but was engaged, open, understanding and never censorious. His faith sustained him in his difficult last years dealing with sarcoidosis and its consequences. Jacob never complained, and always expressed gratitude to his doctors and those who looked after him.

I was lucky to know Jacob, and will always remember his courtesy, kindness, humour, and wisdom.

Hugh Brock

Professor - retired, Department of Zoology, The University of British Columbia

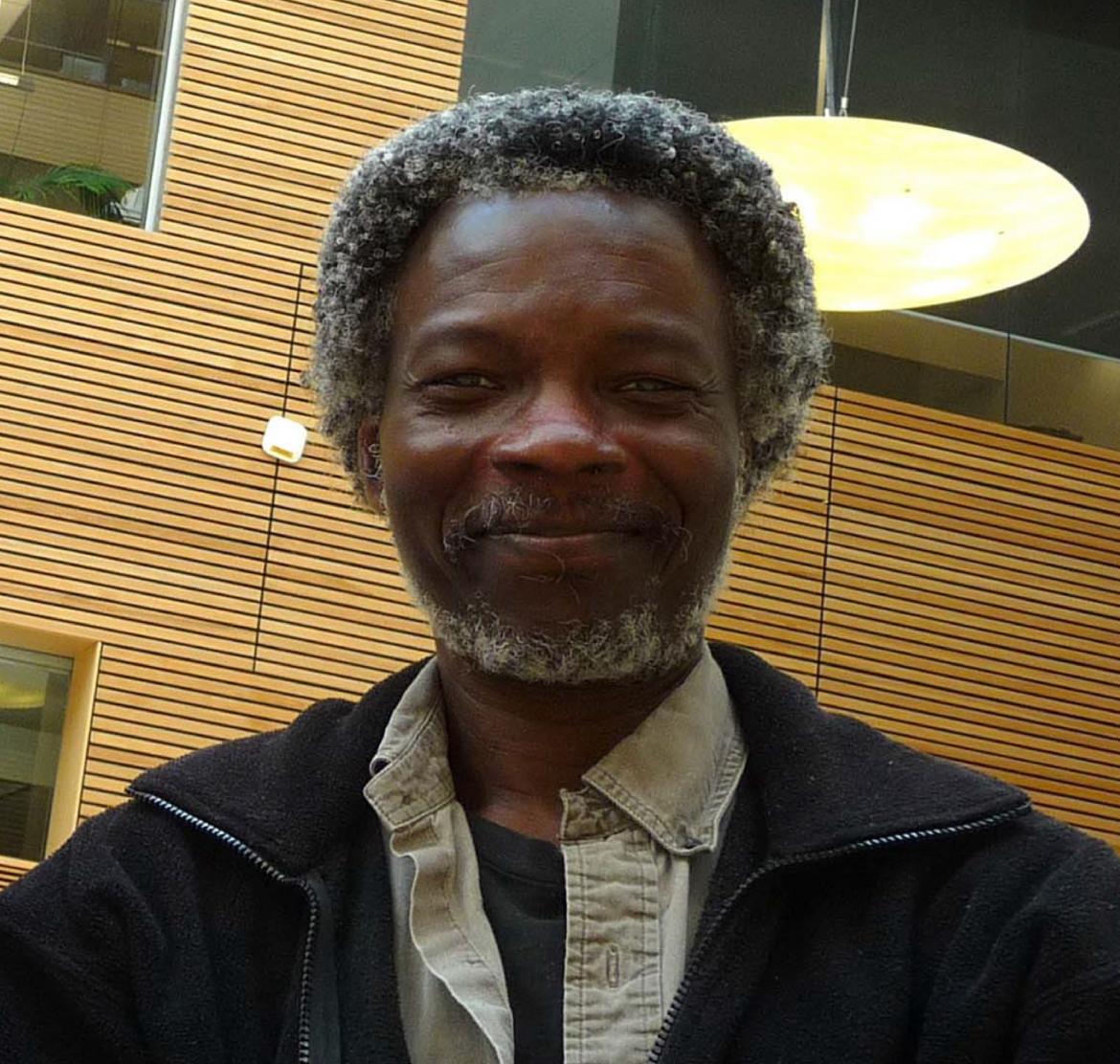

Hugh and Jacob at Life Science Institute - LSI, June 2014 (photo credit: Cynthia Fisher)

_____________

When asked to visualize the Platonic ideal of a scientist, it isn't the Nobel laureates and luminaries in my field that come to mind. Rather, I think of a kindly researcher in his trademark well-worn white coat, cuffs slightly rolled up, ambling the hallways, his mug of tea and deep thoughts in tow. To me, Jacob represented the enterprise of scientific discovery: a sharp wit, a broad and deep knowledge of scientific methodology and literature, who carried with him not a scintilla of cynicism. Instead, he was able to hold onto what really matters in science: the sense of awe and proportion for nature and a keen appreciation for the clever traps we deploy to bottle her up temporarily, just long enough to glean some of her secrets.

I only knew Jacob for a few short years during the tail end of my PhD. During that time, we would chat in the evenings as we waited on western blot incubations. We would discuss topics like the characteristics that defined a truly elegant experiment, or how it might be possible to recreate the lively exchange of ideas that powered the halcyon days of the Immunology Department at Cambridge MRC. For Jacob, these were the essence of science, not as a body of knowledge, but rather as a philosophy for efficiently and elegantly exploring the unknown.

To this day, whenever I stand by a whiteboard and muse over new data, how it impacts our working model and the experiments to follow, I often wonder 'What would Jacob think? Has the question been pared down to its barest, purest form? Are there still excess parts to be trimmed?'. And as I consider these points, I find myself incredibly fortunate to have known such a deep thinking, deeply giving, and brilliant scientist.

Jacob, you will be sorely missed.

Edmund Au

Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology and Cell Biology, Columbia University

_____________

I will always remember Jacob from the time we spent in the Biosciences Building until the later years in the Life Sciences Institute (LSI). He used to call me ‘Doc’, and he would stop by the offices and labs of many to talk. We would talk about the latest new paper he read in the scientific journals, about his martial arts hobby, and other current events. Jacob used to regale me with stories of his years at Mill Hill UK and then later at Stony Brook in Long Island New York. He used to tease me about being from New York City since I did NOT have the New York City accent that he expected. I used to tease him and say that Stony Brook Long Island was NOT New York, but a distant suburb. Then he would laugh and laugh. When the Cell & Developmental Biology labs in ZOOL moved to the LSI, Jacob found a treasure chest of new Faculty, Postdocs, and students to talk with. Jacob would walk the hallways of the LSI in the evenings, when the trainees were working late on their experiments. He would always find friends to talk with. I have been surprised at the number of people who knew Jacob, mostly former trainees. Even when Jacob was ill, he used to come to the LSI to attend the Epigenetics Joint Lab meetings, and then afterwards, or beforehand, he would come by to visit, and ‘Doc’ and Jacob would talk. That is the last memory I have of Jacob….talking and laughing in my office in the LSI. He will always be there doing that in my memory.

Linda Matsuuchi

Professor, Department of Zoology, The University of British Columbia

_____________

I always enjoyed those spontaneous, wide-ranging, hour-long scientific discussions with Jacob, often late at night in the LSC. Jacob’s breadth of knowledge and insights were great, and there was nothing better than getting him laughing.

Mike Gold

Professor, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, The University of British Columbia

_____________

I had the privilege of knowing Jacob for several years while I was a PhD student in the Epigenetics group at UBC from 2010-2016. Jacob was a friendly and engaging mentor and colleague. He was always available for impromptu chats in the hallways where we would discuss anything from critiquing the latest science to career advice and life lessons. He had a sharp analytical mind and an easy-going and down-to-earth demeanour, a rare combination. One of the frequent expressions he would use when discussing research was: “What is the question?” He always stressed the importance of asking the right questions in research. Jacob you encouraged and supported me and many other trainees through the ups and downs of grad school. You helped shape the scientist and person I am today. Thank you, my friend.

Peter J. Thompson

Assistant Professor, Department of Physiology & Pathophysiology, University of Manitoba

_____________

_____________

Our friend Jacob Hodgson will be dearly missed. A fixture in the Zoology Department for decades, he was a one of a kind original. He lived and breathed for two things. Science, and debate. He would do anything for a spirited, passionate debate. Often taking whatever side was necessary to spark one. He was also a kind, generous man, who always had time to share what he knew with others. I, for one, owe half of what I know about molecular biology to Jacob. May he rest in peace.

J. Greg Doheny

Ph.D. RMCCM, Department of Biology, Columbia College

_____________

Jacob was a cherished friend to many and a long term member of our scientific community.

Jacob used to drop by my office on a regular basis when we were in the old Zoology building and later when we were all in the LSI. I have many fond memories of our conversations, which were not limited to science, but also our shared interest in music and especially drumming. We didn’t know we had a mutual interest in drumming until we ran into each other at a Taiko drum concert. From then on that too became a topic for our visits along with the science.

Jacob had the most amazing smile. We lost a very decent man and a wonderful friend.

Don Moerman

Professor - retired, Department of Zoology, The University of British Columbia

_____________

Dr Jacob Hodgson was a brilliant scientist who was a constant presence at the department of Zoology at UBC for countless years. During that time, he provided mentoring, help, and guidance for many, many young graduate students from across many different labs. I was one of I'm sure many who were grateful for his advice and derived great benefit from his help and encouragement. He has my gratitude, and will be missed.

Jaimmie Que

Biology Instructor

_____________

I have many fond memories of deep discussions about evolution and even conservation with Jacob on the old west wing, third floor of the BioSciences Building.

In the old days, groups were much more mixed-up in terms of specialties and office/lab areas. My office was right across the hall from Jacob's lab area and we often

met impromptu in the hallway. We both worked with genetic tools/approaches from very different perspectives and I was always amazed at Jacob's enthusiasm for topics like

speciation and the detail of the genetic manipulations that he was practicing in flies. I also most fondly remember Jacob's great smile and his sonorous laugh!

Rick Taylor

Professor, Department of Zoology, UBC

_____________

Jacob was my first and most influential in-lab mentor. I was honored and blessed that Jacob welcomed undergrad me as a scientist and friend. I fondly recall our many shared nights experimenting, chatting, and listening to Bob Marley. Jacob approached science with an inspiring mix of unbridled enthusiasm and rigor. The purest scientist I've ever met. Jacob’s imprinted teachings and style will forever guide my own research and mentoring.

With shared condolences and reflections,

Kryn Stankunas

Associate Professor of Biology, Institute of Molecular Biology, University of Oregon

_____________

I knew Jacob when I was a young MSc student in Hugh Brock’s lab studying Polycomb group proteins. I fondly recall many late night conversations with Jacob that were equal parts inspiring as well as entertaining. The crucial topics we covered included such things as the importance of having hobbies that took you away from science from time to time; why Drosophila development was such a great system for better understanding the basic principles of human cancer (the past 20 years of research has strongly confirmed Jacob’s faith in this); and telling stories about famous scientists that Jacob had met/worked with throughout his career. Through his actions, Jacob also imparted a pure enjoyment and passion for answering scientific questions, and the importance of getting the data right. Jacob’s influence spread beyond the Brock lab, as we often had visitors from other labs (sometimes that we didn’t recognize and weren’t sure what department they were from) coming to ask him for advice. I kept in touch with Jacob over the years, although less so in more recent times, but I can still honestly say that in terms of pure skill Jacob was among the top scientists I have ever worked with. And was definitely one of the most warm hearted.

Thomas Milne

Associate Professor of Haematology, Radcliffe Department of Medicine, University of Oxford

_____________

_____________

Jacob was one of the most memorable people in my time as a grad student at UBC. Everybody knew Jacob; he was always there, always willing to hear about the ups and downs of my (and everyone's) projects, always ready to help by sharing tips and tricks, ideas, and his wisdom on how to navigate science and academia. Jacob seemed interested in everything, read everything, and was able to engage in enthusiastic and stimulating conversations about everything - a true, selfless scientist, and a wonderful colleague.

Pamela Kalas

Associate Professor of Teaching, Departments of Zoology and Botany, UBC

_____________

Quite often, and usually when I was sitting on a grant or paper revision deadline, there would be a knock at my office door – “Do you have a minute?” When it was Jacob, I always made sure that I did, but it was never, ever, only a minute. 30 mins or maybe an hour later, we would have discussed a new assay or finding in histone acetylation or DNA methylation he wanted to share, or get a second opinion on – that would sometimes be timely enough to squeak into my work-in-progress grant revision. Or a new theory he wanted to pick apart, and needed a little back-up; or some scientist who seemed a little full of him/herself espousing ideas that were passe but he didn’t want to appear too critical; or to challenge dogma just a little; or to see what I thought about the new Nobel prize announcement, Nature paper, or a potential recruit. Or to tell me how much he had enjoyed talking late the evening before with one of my grad students, and how impressive they were. Or to share a laugh, a story, an insight, and sometimes (after I adopted my youngest, African, son) a hug.

Jacob was not officially “a professorial colleague.” He was a colleague’s Research Associate, and he was a Prince of a man - and more of a true “colleague” to me than most of the profs whose labs were based around ours. Working on neural stem cells and glia, and mechanisms of epigenetic regulation in nervous system development and its repair, I always felt like a bit of a fish out of water in a Dept. surrounded by eminent Zoologists and evolutionary biologists. But Jacob was the guy who made me feel like we had really smart friends next door who cared about the same things we did, and all of the people in my lab loved it when he showed up – even coming to lab mtgs now and again when the topic was one he was passionate about. Becoming a surrogate lab member on and off, his many passions for science – its practice, its theory, its controversies, and debate – may have been the thing that set him apart from most of the people around us. His polite and gracious demeanour, his quiet chuckling humour, his deep love of science and how it interfaces with the world around him. Heart-felt discussions as to how we both reconcile our personal faith with our science. The list of things that fascinated Jacob was endless. Without having any grad students or postdocs “of his own” he took the time to listen to, and talk with, mine, and even show up to their thesis defenses. He made all their lives richer for it, and there are next-gen scientists who came through my who are now lab spread across the world whom he touched, inspired, and helped along the way. They all have “Jacob stories” they have carried forward into their own science lives. I hope Jacob left this earth knowing how much he had meant to all of us in the Roskams lab, and how our lives were changed by his class, gentle passions, and constantly questioning nature. Although we haven’t seen each other in a while, my heart broke just a little when I heard our paths would no longer cross, and I now join our world of science mourning the loss of Jacob - a gentle, sage, caring, and thoroughly decent human being.

Jane Roskams

Professor - retired, Department of Zoology, The University of British Columbia

_____________

Jacob brightened my days, but especially my nights, as a PhD student struggling through the trial of “generating data”. Being in the same room with such a friendly face and being exposed to the nonstop drumbeat of upbeat, optimistic chatter and banter, and the occasional caffeinated soliloquy, and the laughing – Jacob’s high-pitched convulsive howling, me snickering through one of Jacob’s opinionated rants, the two of us snorting and giggling at the end of one of those discussions where we worked the other up in tandem – these did wonders to chase away the boredom of endless minipreps and OD measurements, and the dejection of so many westerns and even agarose gels that refused to reveal the bands that would let me graduate. Because it seemed mainly to happen at 1 am, Jacob was usually the first person who shared the triumph of a film exposure that revealed a band that told us something interesting about what these proteins were doing. Having such an enthusiastic comrade to share these successes with made them much the sweeter.

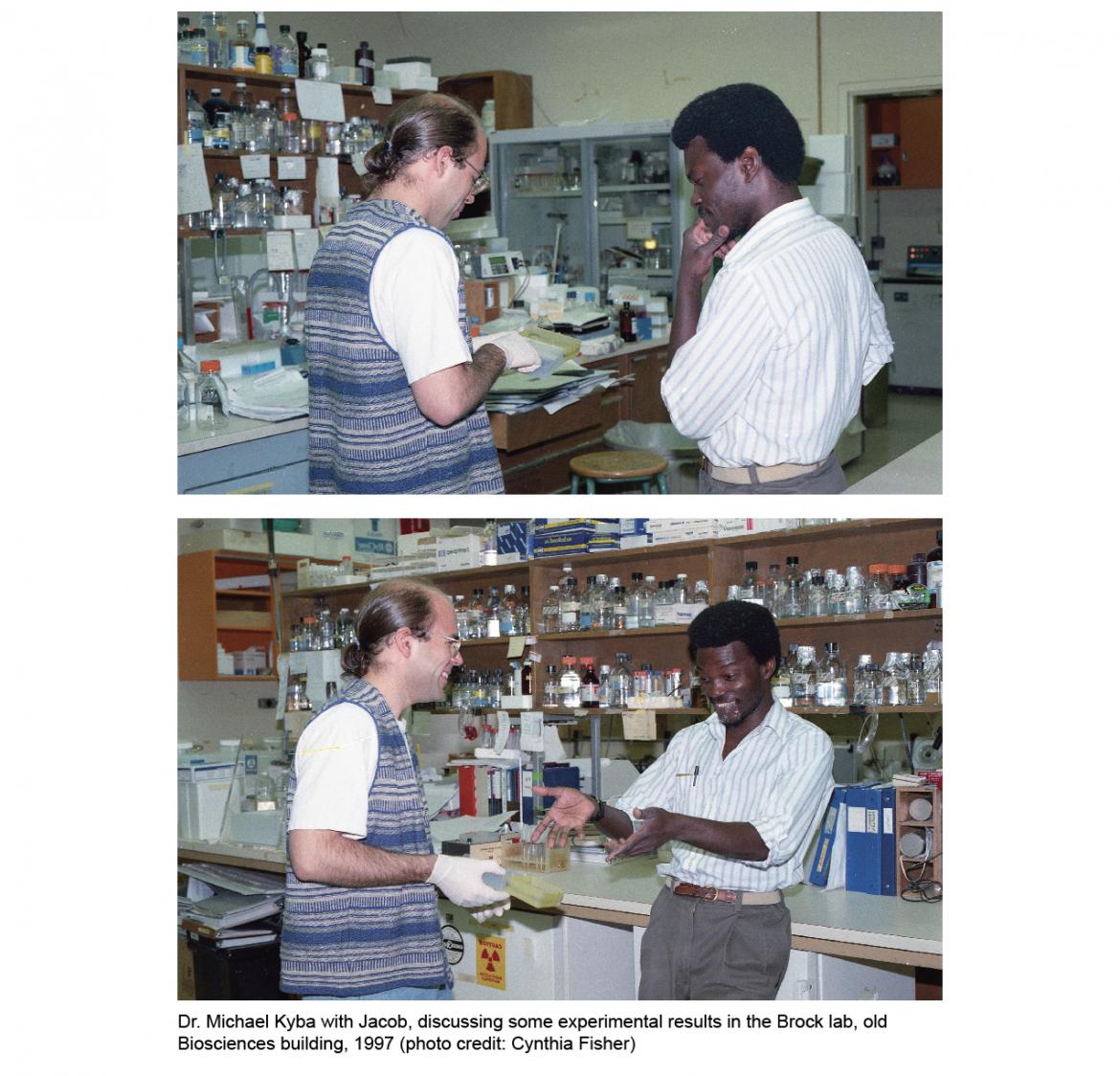

At some point, we figured out that the Polycomb group proteins stuck to each other, and which parts connected to which, but up to when I left the lab, we had little idea of how this might lead to silencing of the genes they regulated. In my thesis I speculated that their large size might provide a steric hindrance, preventing other proteins from accessing the DNA. When Jacob read the draft, he said to me, giggling, “So, you’re saying that these big proteins… glom up the DNA… and polymerase can’t get in?”, the giggling turned to eye watering hiccupping and howling, and after 20 seconds when he got his breath back, he said, “Mike, that’s the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard!” and started laughing all over again. Even though I thought he wasn’t giving the idea a fair hearing, I found myself laughing along with him, almost in tears. Of course, I wouldn’t be dissuaded, and left the (now we know, incorrect) speculation in my thesis. Honestly, I believe I left it in because it made Jacob laugh so hard.

Jacob loved jazz, and it was the background accompaniment to everything going on in the lab after 9 pm. Although his tastes were eclectic, when he was sharing the night shift, he wanted his lab mates to be enjoying the music as much as he was, so he was an accommodating ambassador. He saw that I couldn’t handle too much of his abstruse stuff, so he introduced me to Dave Bruback and to Sonny Rollins. They would make their appearance every night, usually multiple times. To this day, the happy melody of “St. Thomas” takes me back to nights in the lab, pipette pumping, lids flipping, discussing science, politics and religion with Jacob on the other side of the bench, the hours just melting away.

Jacob was a magnificent charmer. Shortly after he arrived in the lab, he asked me where there were labs that did serious biochemistry. I didn’t know what he meant – serious biochemistry. Anyway, I thought of the labs in the connected, very modern building that was attached to our ancient one. Being around midnight, the connection between the buildings was locked, but for some reason I had a key. I let him in and walked through to show him the location of one of the labs that I thought might be doing what he was interested in. He wanted to explore more, so I headed back to the lab. When he came back an hour later, his eyes were big. “Mike, I found these columns! They’re big – I can use them to do some real biochemistry!”, his head nodding with approval and smiling at the notion. Then, a few days later, he showed up in the lab, beaming, with these gigantic columns that he had talked somebody into letting him borrow. I don’t even know if he ever used them – we probably couldn’t have afforded the amount of sepharose they required. But for a long time they were there in the lab as an aspiration. The message was: think big! Do something that will really matter! Even if it fails, and it usually does, the point is the trying. That infectious optimism and the attitude of embracing the struggle was invaluable for me, and I am sure for many other students in the lab.

Jacob, you were a blessing to me, and a catalyst to friendships on the floor, and a glue to the community you were a part of. May God bless you and keep you.

Michael Kyba

Professor, Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota

_____________

I first met Jacob when I joined Hugh Brock’s lab as a PhD student in September 1996. I initially found Jacob to be intimidating, he was so dedicated to his work, so knowledgeable, and seemed so serious. However, that feeling of being intimidated didn’t last long! Once I got to know him a bit better, Jacob revealed the other side of his character, that of an incredibly generous, kind, and humorous soul. Jacob used to work long hours, late in the lab each evening, drinking copious amounts of black coffee brewed in Tom Grigliatti’s lab down the hall in the old Biological Sciences Building, and it was during the late night stints that I shared with him, where the roots of our friendship grew.

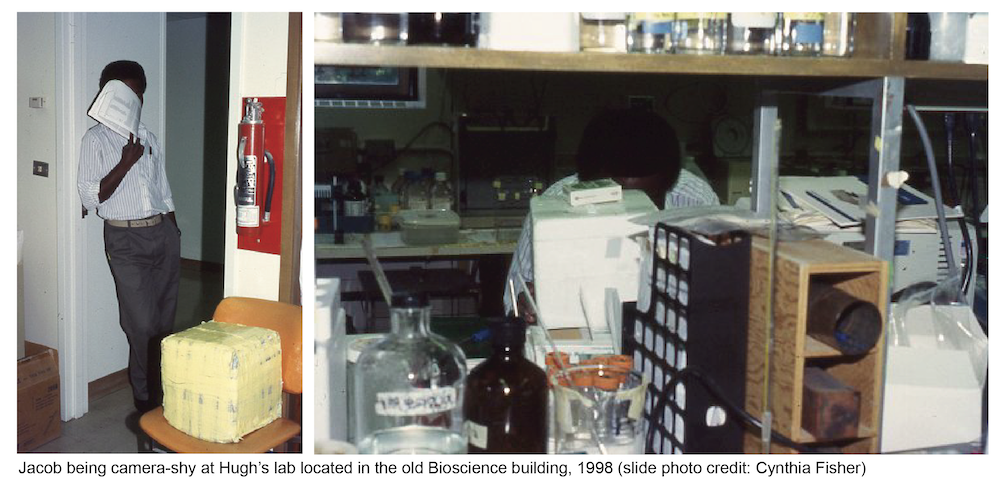

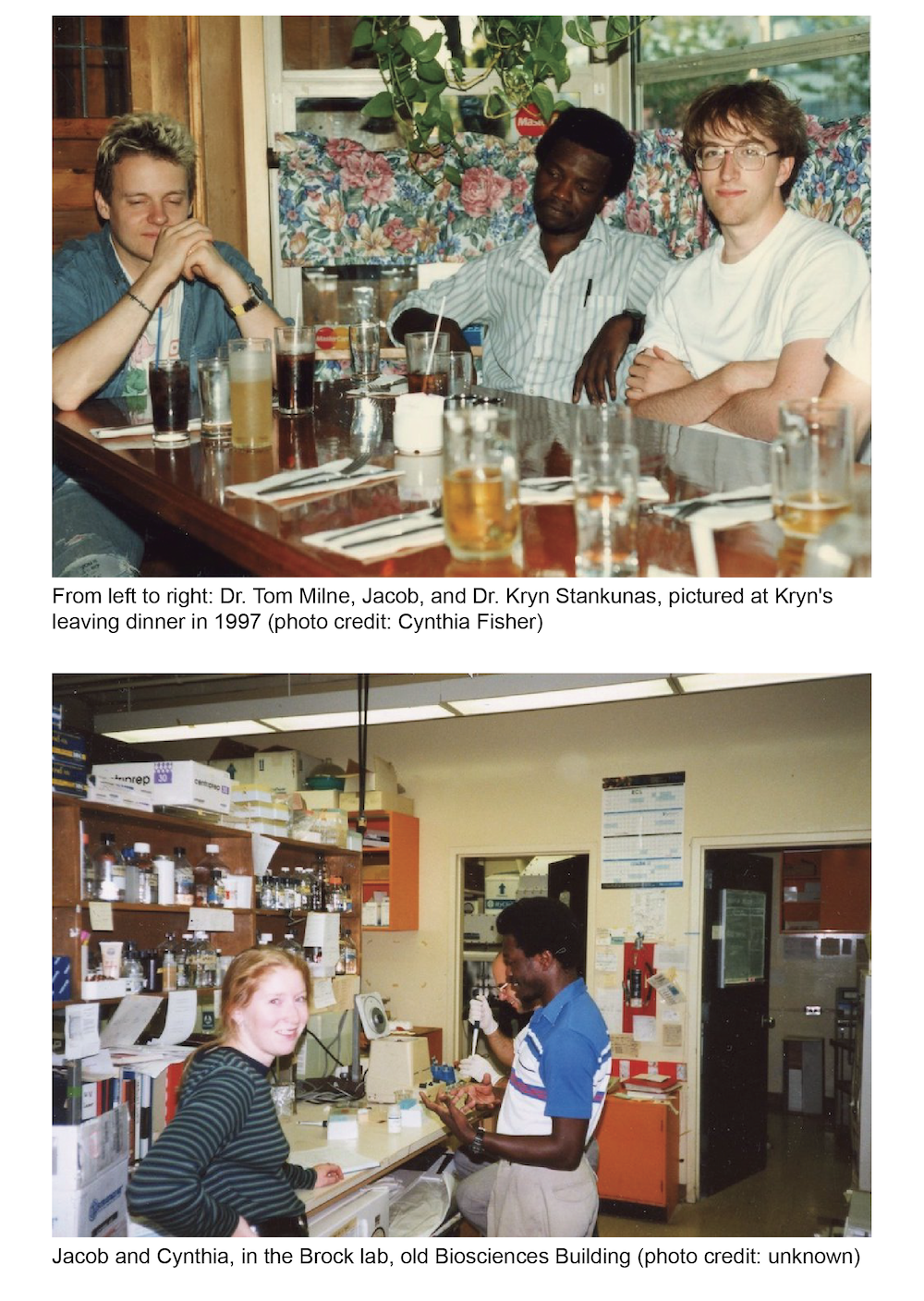

Lab group photo from 1997. Apparently, Jacob had this photo in his desk drawer in the Brock lab in the LSI building, and it was found when colleagues from the Lorincz lab were cleaning out his desk after he went into hospital. They gave it to me after I'd started working at UBC again. I sent Jacob a copy, which he was happy to have. I don't recall everyone's names in the photo (perhaps Hugh can help me out here) but from top to bottom, left to right: (top) Dr. Michael Kyba, Dr.Cynthia Fisher, …., Dr. Hugh Brock, …., Dr.Kryn Stankunus; (bottom) Dr. Ester Falconer (maiden name O'Dor), Dr. Tom Milne, Dr.Jacob Hodgson. (photo credit: Kryn Stankunas, caption: Cynthia Fisher)

We used to walk over to the University Village food court in the basement to get supper, when that was one of the few options on campus to buy food in the evening. Jacob would spray lashings of hot sauce all over his food each time, I wondered how his taste buds could still function. After Hugh left in the evening, Jacob would blast music in the lab on the CD player, and I gained a true appreciation for jazz music as a result. Miles Davis’ “Kind of Blue” album was a favourite, along with Dave Brubeck’s “Take 5”, and Jacob would discuss the intricacies of the artists’ musical creativity and impact. Jacob played the flute, and also practiced martial arts, and one couldn’t help but wonder if this helped shape his mental fortitude and stamina. Jacob, having received his graduate education in the UK, and picking up several British-isms, introduced me to the British condiments Marmite and Branston Pickle, each of which he kept a jar of in the office fridge, and often made proclamations about their fine taste (to which I typically responded by making a face of disgust). I didn’t end up acquiring a taste for the peculiar Pickle substance until I after moved to the UK in 2005 for postdoctoral work! Jacob never converted me to being a Marmite lover, despite many attempts. He also clearly loved British cheese (which is far superior to Canadian cheese, I have to agree!).

Jacob’s laugh was hearty and infectious, and his never-ending sense of optimism and positive attitude was inspiring. Long conversations on varied topics, inevitably coming back around to science, would occur on any typical evening in the lab. Jacob had an almost encyclopedic knowledge of his field, kept stacks upon stacks of papers on his office desk and shelves, was clearly passionate about science, would love to discuss experiments and theories, and rip apart journal articles that he felt weren’t good enough. He loved to tell stories about his past research, mentors, and scientific experiences. He was always there to support the trainees in the lab, whether it be on a topic of a personal nature, difficulties in dealing with the stress of the academic environment, career development advice, or reviewing a poster abstract, presentation, award application, or really anything at all to do with scientific communication.

Jacob never sought the limelight. On the contrary, he was happy to pursue scientific research at a high level without any fanfare and yet with determination, commitment, and passion, lifting up the trainees and colleagues around him over many years, to help enable their career trajectories. Many former trainees in the Zoology Department and beyond owe a debt of gratitude to Jacob, myself included, and the successes we have gone on to achieve in our careers are his successes.

I was saddened to learn of Jacob’s ill health upon my return to Vancouver and UBC in 2017, yet felt fortunate to re-kindle our friendship then. We shared many phone and WhatsApp conversations over the past few years, and I was able to see him a few times in hospital (smuggling in some British cheese!) or the care home where he lived more recently, with one highlight being meeting up at a jazz show at the Shadbolt Centre in Burnaby before the pandemic. We reminisced about our time together in the lab. I gave him updates when I could, about former Brock lab members, and links to epigenetics research webinars during the pandemic, and he remained the eternal optimist, coming up with several ideas that could enable him to return to the research sphere in some form. He felt positive that his condition would improve and that he could move out of the care home eventually, and get back to work. His constantly positive outlook and bright spirit was uplifting and remarkable, especially in the face of adversity.

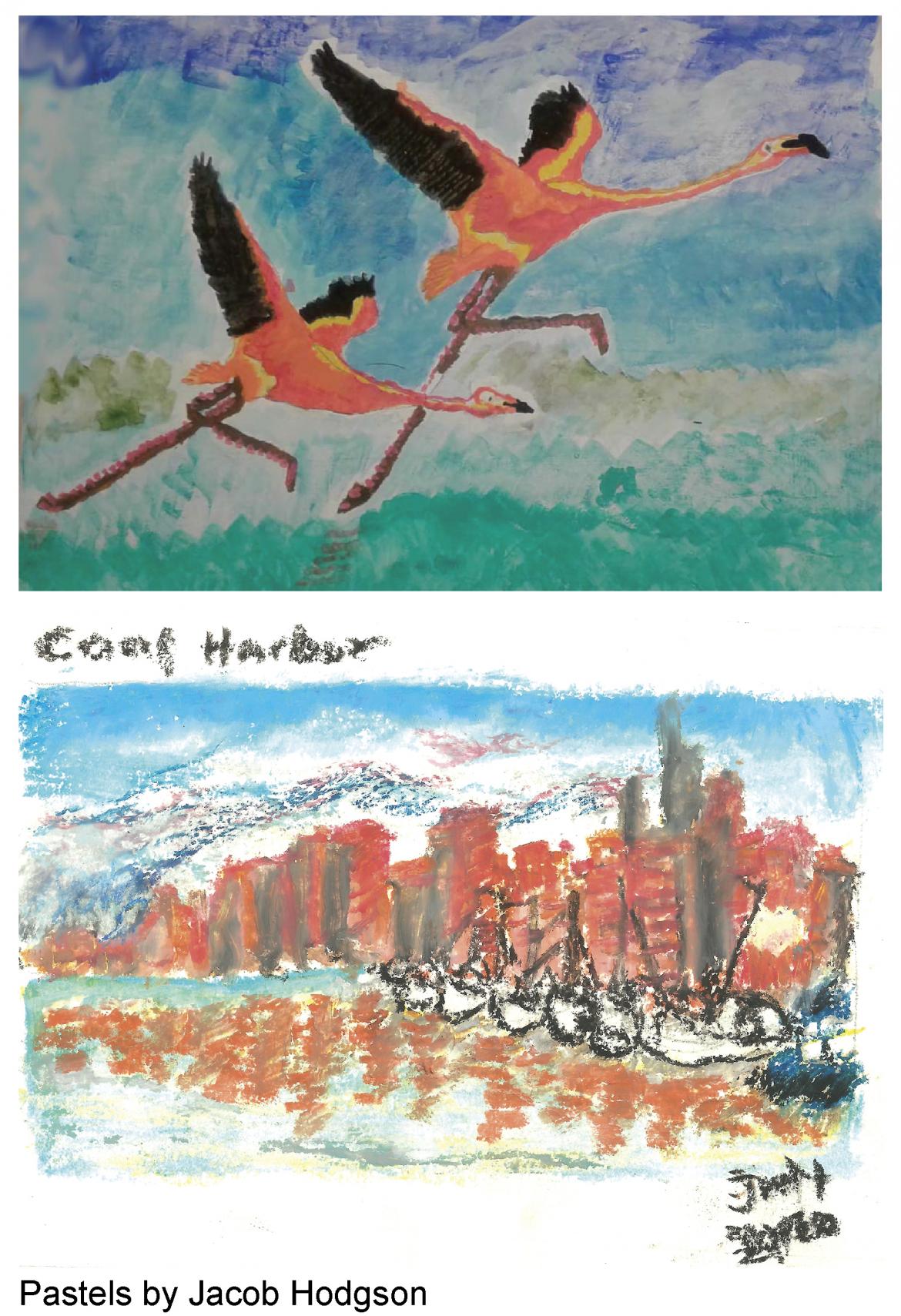

The last time I saw Jacob in person was in May of this year. I brought him some strong black coffee and a scone and he was so happy – apparently the coffee in the care home was not up to his high standards! In recent years, ever musically-minded, Jacob had taken up drum lessons, and played in a performance group at the care home. He also immersed himself in sketching and drawing with pastels, he proudly showed me some of his artworks, and expressed his love for vibrant colours and traditional African print patterns. During this last visit he also expressed his gratitude for being in Canada with its excellent public health care system and how it took care of him. He shared more memories of his research training journey and reasons for leaving Ghana to expand his horizons. He also expressed how proud he was of what the former Brock lab trainees have achieved in their careers, going on to key positions in academia and industry. He asked me to send his greetings to our former research colleagues – so from Jacob to me to you reading this now – know that Jacob was thinking of you. The best way we, as Jacob’s former colleagues, can honour his memory is to lead our lives as he did – in the service of others and the pursuit of scientific excellence. Rest in peace, my dear friend Jacob, you will be missed.

Cynthia Fisher

Research Associate, School of Biomedical Engineering, The University of British Columbia

Hugh, Cynthia and Jacob at Life Science Institute - LSI, June 2014 (photo credit: Cynthia Fisher)